The water was neither blue nor green, but a little brown. It was November, and our family and my parents were at the coast together. I love that line, perhaps because I have always loved pictures taken from behind, like the one of me carrying my son to the sea for the first time. It was more than a week into learning Clifton’s poem that I realized the ninth line was not “love you back” but “love your back.” As in, I love the part of you that is turned from me. But somehow it’s easier to release things when we stand at the water’s edge, “the lip of our understanding.” In Clifton’s hands the tiny word “may” encompasses every interpretation. The word “may” means many things, from possibility to certainty. In “blessing the boats,” the words “May you” are a repeated blessing: Jones, who treasures Clifton’s poems so much that she has purposely not yet read every one. I decided to learn one of Clifton’s poems by heart after interviewing poet Ashley M. Clifton’s star has only shined brighter since her death in 2010, and I believe it will become brighter still, much like Emily Dickinson’s.

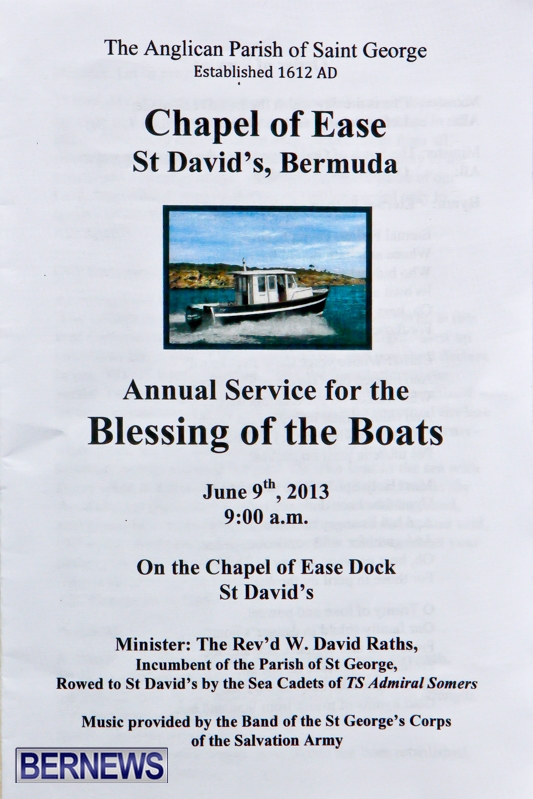

Although Clifton’s poetry was recognized in her lifetime - she was nominated twice for the Pulitzer and served as poet laureate of Maryland - I don’t think she was recognized enough. Lucille Clifton is one of our Take Your Poet to Work icons. The rocks to the right fade into the green waves, which will stop crashing as the boat reaches deeper water, and the water turns to blue, and the blue will be blessed by the sun (rising or setting, the painting doesn’t say).

I can put myself in two places simultaneously: the person in the boat, about to sail away (the one being blessed), and also the person on the shore, about to wave goodbye (the one giving the blessing). For my parents, it symbolized the Chilean sea where they first kissed. Forever after, Lucille Clifton’s “blessing the boats” will be associated with the last thing I took from my dad’s house - a painting titled “Nosotros” by L.Y.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)